|

Caine & Caine (1997) explain the interconnectedness of the brain:

Caine, R. & Caine, G. (1997). Unleashing the Power of Perceptual Change: The Potential of Brain-Based Teaching. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. pp. 6-7.

1 Comment

Michael Fullan and Geoff Scott suggest that a feature of the new pedagogies for deep learning is of teachers and college professors becoming:

1 Fullan, M. & Scott, G. (2014). Education Plus. Seattle, WA: Collaborative Impact SPC. p.7.

Fullan (2015) describes leadership from the middle as:

Fullan, M. (2015). Leadership from the middle: A system strategy. In Education Canada (55)(4). pp. 22-26. Canadian Education Association.

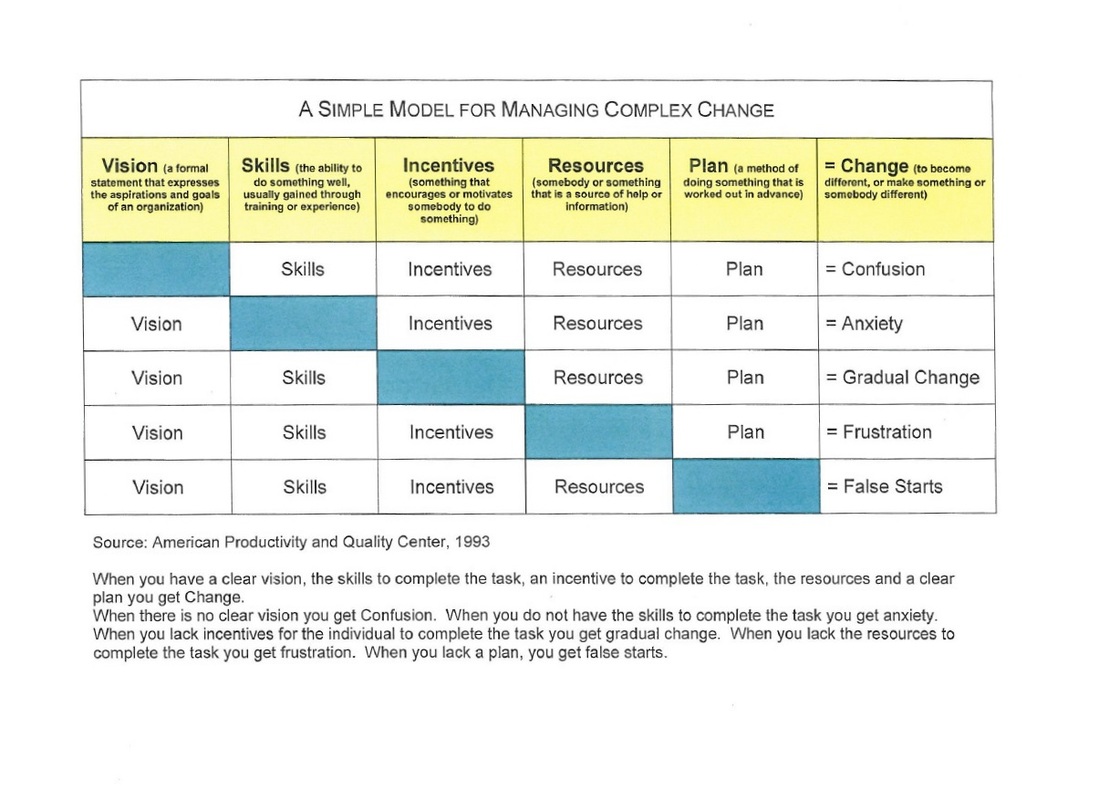

American Productivity and Quality Center. (1993). A Simple Model for Managing

Complex Change. Houston, Texas. The following is a list of readings that we found useful when formulating our philosophy:

Key to personalised learning is the changing nature of assessment. No longer simply a performance measurement, assessment is used gather information that will help to identify student learning patterns, strengths and weaknesses, in order to further customise learning.

To power personalized learning, assessments should encompass a broader range of measures beyond performance on academic tests, including information on a student’s learning style preferences, previously successful experiences, interests, and other factors in a learner’s life. 1 During a U.S. Summer Seminar in 2012, Richard Culatta defined personalizing learning as a way if individualizing learning for each student in the room by adjusting the pace, adjusting the approach, and leveraging students’ individual interests and motivations.2 His examples of personalised learning included:

1 Wolf, M.A. (2010). Innovate to Educate: System [Re]Design for Personalized Learning. A Report from the 2010 Symposium. Edited by Partoyan, E., Schneiderman, & Seltz, J. ACSD. p.25. Retrieved from https://siia.net/pli/presentations/PerLearnPaper.pdf

2

The increasing availability of digital technologies is rapidly changing the nature of learning:

“Digital technologies change the way students learn, the way teachers teach, and where and when learning takes place. Increasingly, mobile devices equip students to take charge of their own learning in a context where learning occurs anywhere, anytime, and with access to a wealth of content and interactive tools. Digital technologies can excite and engage educators, students, their whānau and communities in learning."1

An OECD report, 'Skills for a Digital World', provides new evidence on the effects of digital technologies on the demand for skills and discusses key policies to foster skills development for the digital economy:

“In addition to digital literacies and ICT-specific skills, the identification of the skills relevant for the digital economy and of the strategies to develop them is entrenched with the notions of higher order thinking, communication and social skills.” 2

1

2

In John Hattie's recent work, 'What works best in education: the politics of collaborative expertise', he argues that

"...the greatest influence on student progression in learning is having highly expert, inspired and passionate teachers and school leaders working together to maximise the effect of their teaching on all students in their care." 1

In order for this to be accomplished, Hattie proposes that more emphasis needs to be placed on reducing the' variability among teachers in the effect they have on student learning' by collectively raising the standard:

“…we need to recognise effectiveness among teachers and build a profession that allows all to join the successful." 2

He believes this variablity can be reduced by creating

"...a system where leaders know their high-impact teachers so that they may create a coalition of the successful who can work together on reducing within-school variability." 3

1

2

3

"Do you ever find that young people, when they have left school, not only forget most of what they have learnt (that is only to be expected), but forget also, or betray that they have never really known, how to tackle a new subject for themselves? 1

- Dorothy Sayers 1947

LEARNING TO LEARN

One of the key elements of personalised learning is teaching students HOW to learn. 'Learning to learn' is a key component of the New Zealand Curriculum, with "complex problem solving, communication, team skills, creativity and innovation recognised as necessary skills for success." 2

The New Zealand Curriculum identifies five key competencies:

Similar key competencies are outlined in countless articles and research documents, with the focus of key competencies more recently centred on digital literacy. Eric de Corte, as quoted in The 21st Century Learning Group report (2014) identifies a number of areas in which education needs to develop in order to sufficiently prepare students for the future: “One dimension is the need to instil creativity, collaboration, problem-solving and entrepreneurial approaches. A second is to build digital literacy and media literacy. A third is to develop ‘adaptive competence’ — the ability to apply meaningfully learned knowledge and skills flexibly and creatively in different situations.” 3

EXAMPLES OF KEY COMPETENCIES

The Four R's

In Guy Claxton's book 'Building Learning Power', he outlines four key habits of the mind that are evident in successful learners:

The Six C's

Michael Fullan and Geoff Scott (2014) propose that learning goes beyond the development of fundamental skills and knowledge, to include the development of 'personal, interpersonal and cognitive capabilities that allow one to diagnose what is going on in the complex, constantly shifting human and technical conteext of real world practice and then match an appropriate response.' 4

Their model includes 'the Six C's':

What does this mean for us?

The consensus is that we need to equip students to be able to adapt to their uncertain and everchanging future environment. Therefore, changing our emphasis in education from teaching content to teaching skills is vital. Students will need to develop skills in:

King Solomon's statement "there is nothing new under the sun" (Ecclesiastes 1:9) is true for education today as we reflect on Dorothy Sayer's observations over 70 years ago:

"For the sole true end of education is simply this: to teach men how to learn for themselves; and whatever instruction fails to do this is effort spent in vain." 5 1 Sayers, D. (1947). The Lost Tools of Learning. Presented at Oxford. Retrieved from https://www.gbt.org/text/sayers.html 2 NZ Ministry of Education. (2015). New Zealand Education in 2025: Lifelong Learners in a Connected World [Discussion Document]. New Zealand: Author. 3 NZ Ministry of Education. (2014, May). Future-focused Learning in Connected Communities. New Zealand: 21st Century Learning Reference Group., p. 33. 4 Fullan, M. & Scott, G. (2014). Education Plus. Seattle, WA: Collaborative Impact SPC. pp.6-7 5 Sayers, D. Ibid.

Credit flexibility provides an avenue for 'gifted' or 'accelerated' students to access advanced coursework when they are ready for it, and helps to alleviate potential issues such as demotivation or boredom while they wait for their peers to 'catch up'.

Schools worldwide are increasingly moving towards competency-based assessment as their educational governing bodies make fundamental changes to the way academic credit is awarded. With this change in assessment comes increasing flexibility in the method and timing of assessment. In the United States, Oregon continues to be leading the implementation of credit flexibility and is encouraging districts to award academic credit based on mastery rather than seat time. Since 2002, the state policies allow districts to award credit based on proficiency.1 The Ohio State Board of Education has also adopted a plan to empower “students to earn units of high school credit based on a demonstration of subject area competency, instead of or in combination with completing hours of classroom instruction.”2

New Zealand is well on the way to improving its assessment strategy, and perhaps one day soon will realise Claire Amos' idea of a national assessment framework that:

...was not just same old subjects ‘anytime, anywhere’ but rather key competencies demonstrated ‘anytime, anywhere, anyhow’.3

By harnessing the opportunity digital technologies provide in gathering assessment data over a period of time and in the creation of portfolios of learning, students will be able to achieve credit for competency when they meet the criteria, without having to wait to sit an examination or achieve the prescribed age.

We are excited by these future possibilities, and by NZQA’s key goal of having ‘NCEA examinations online, where appropriate, by 2020’ 4, as these will enable gifted or accelerated students early access to coursework and examinations. 1 Frost, D. (2016). Moving from Seat-Time to Competency-Based Credits in State Policy: Ensuring All Students Develop Mastery. Competency Works. Retrieved from https://www.competencyworks.org/understanding-competency-education/moving-from-seat-time-to-competency-based-credits-in-state-policy-ensuring-all-students-develop-mastery/ 2 Hanover Research. (2012, October). Best Practices in Personalized Learning Environments (Grades 4-9). Washington, DC: Author. p.20 3 Amos, C. (2014). The Biggest Challenge Facing Education. Education Review - Sector Voices. New Zealand Media & Entertainment. Retrieved from https://www.educationreview.co.nz/news/2014/sector-voices-the-biggest-challenge-facing-education/ p.29 4 NZQA Statement of Intent 2016/7 - 2019/20 https://www.nzqa.govt.nz/about-us/publications/strategic-documents/soi-1617-1920/assessment/ |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed